However, it must also be considered that The actual requirements for a population to survive with a given amount of members are far more complex, relating mainly to the space needed for habitation (much larger than mere existence in stasis), and the availability of resources. Given substantial space, as population increases, there are less resources available for each individual. Population increases until a carrying capacity (K) is met, at which point population oscillates around the carrying capacity.

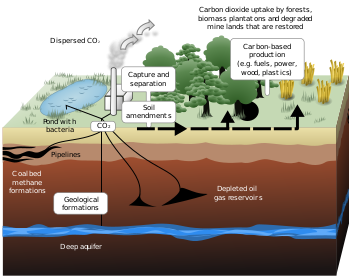

Additionally, the survival of humans relies heavily on the level of impact we have on the planet. This impact is demonstrated in the I=PAT (Impact = Population x Affluence x Technology) equation, developed in the 1970's by Paul Ehrlich and John Holdren. This equation describes how humans impact (I) the planet. The greater the three factors (P,A,T), the more impact humans will have on the environment. As population (P ) increases, humans use more land and resources, and pollution generally increases as a result. When affluence (A) increases, the environment is further impacted by higher rates of consumption, which lead to more environmental impacts, however, one could argue that affluence also can reduce environmental impacts if those affluent are inclined to use their wealth for the benefit of the environment. Finally, technological increases (T) can have a similar effect of affluence in increasing efficiency of the utilization of resources, however, with increases in P, the utilization of technology necessarily increases, greater impacting the environment. In order to continue our survival, we must control our impact on the environment, which will require the proper management of population, affluence, and technology. As these currently high population, low emissions develop, their emissions will increase substantially, and if the population problem is ignored until this point, we will face a colossal issue when this comes to be.